Article by the Drummond Team

Extreme stress can be linked to heart disease, diabetes and depression, however, small doses are crucial for developing resilience. For example, being requested to attend an urgent meeting, or your taxi inching towards the airport with minutes to spare before your flight makes your heart pound & your stomach lurch, makes your hands turn clammy: the effects of stress are visceral and instantaneous.I

When faced with a perceived threat, the body’s fight or flight system triggers in a well-choreographed sequence that has evolved over millions of years. “We’re here because our ancestors were so brave and could survive through times of terrible stress and threat,” says Carmen Sandi, who leads a behavioural genetics laboratory in Switzerland. “The problem nowadays is that we’re activating this ancient survival response in a job interview.”

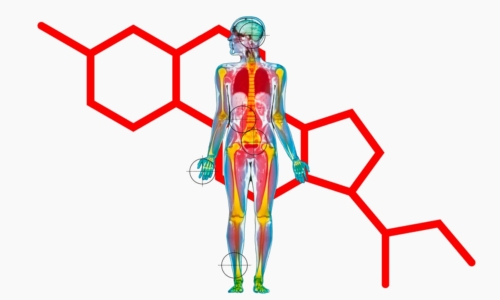

In the modern world, where life-threatening situations are encountered rarely, stress itself has become the spectre. Last year, in the largest survey on the impact of stress, three in four Britons reported being so stressed that they had felt overwhelmed or unable to cope at least once over the last year. Studies across populations have linked extreme and chronic stress with heart disease, diabetes and mental health problems including depression. What is it doing to our bodies?

Adrenaline rush

Blood is shunted away from the digestive system towards our arms and legs and the muscles around our small intestine contract, creating the feeling of a knot or fluttering in our stomach. For reasons that are not entirely understood – possibly the body’s way of trying to remove any harmful toxins – adrenaline loosens the bowel muscles, meaning that acute stress can leave us racing for the bathroom. Another unwelcome side-effect is sweat, which is more sudden and smells worse than the kind produced during exercise or in hot weather. While exercise sweat comes from the eccrine glands and contains mostly water, adrenaline activates the apocrine glands in the armpits, which release a milky-looking substance containing fats and proteins, fuelling bacteria.

Adrenaline also prompts a massive mobilisation of immune cells, which travel from the spleen and bone marrow where they are stored, into the bloodstream. “There’s an evolutionary theory that in the past social stress was often a predictor of trauma or violence,” says Ed Bullmore, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Cambridge, who is exploring the link between stress and the immune system. “When I’m standing up doing a public presentation, my [subconscious] looks at all these people staring at me and says ‘Maybe they’re going to attack’ – so my immune system ramps up in advance.”

While adrenaline floods the body within seconds, a second stress hormone, called cortisol, seeps into the bloodstream more gradually, peaking after 20-30 minutes. Cortisol changes the metabolism of cells, how cells function and alters the activity of DNA. In the brain, cortisol binds to neurons, altering normal thought processes including the way stressful events are recorded in our memories. Neuroscientists think the influence of cortisol could explain why our memories of traumatic or highly emotional events are often exceptionally vivid.

Is stress always bad?

Research suggests that some stress exposure is crucial for developing the resilience that allows us to cope with unexpected and challenging situations in the future. A 2013 review entitled “Understanding resilience” draws parallels with the way exposure to germs boosts the immune system, concluding: “Stress inoculation is a form of immunity against later stressors, much in the same way that vaccines induce immunity against disease.”

Adrian Wells, a professor of clinical and experimental psychopathology at the University of Manchester, agrees. He is concerned that the negative effects of stress are sometimes exaggerated and that an “epidemic of stress phobia” is turning situations that ought to be challenging or even exhilarating into something altogether more traumatic.

The pursuit of a stress-free life is not healthy. It is like exercise. It’s uncomfortable, but it helps you build stamina & strength

Source: The guardian.co.uk