High intensity interval training is a popular training method used in fitness, sport and exercise programming. It is used to target improvements in cardio-respiratory fitness, metabolic function and performance.

Definition: Whilst there are a variety of forms of HIIT, all involve repeated short to long bouts of high intensity exercise interspersed with active or passive recovery periods.

Which variables you manipulate or chose to programme is dependent on the optimal stimulus required for the long or medium term adaptations required to the layers of the cardio-vascular system. Either peripheral adaptations (increased use of oxygen by the working muscles) or central adaptations (increased delivery of oxygen to the working muscles). The adaptations that will occur both at cellular level and systemic level are specific to the characteristics of the training programme you use. This can be manipulated using 9 variables.

Variables

Various variables can be manipulated to design a HIIT programme. Remember there are hundreds of ways to skin the cat and we have selected only a few in this article. They are by no means the only methods.

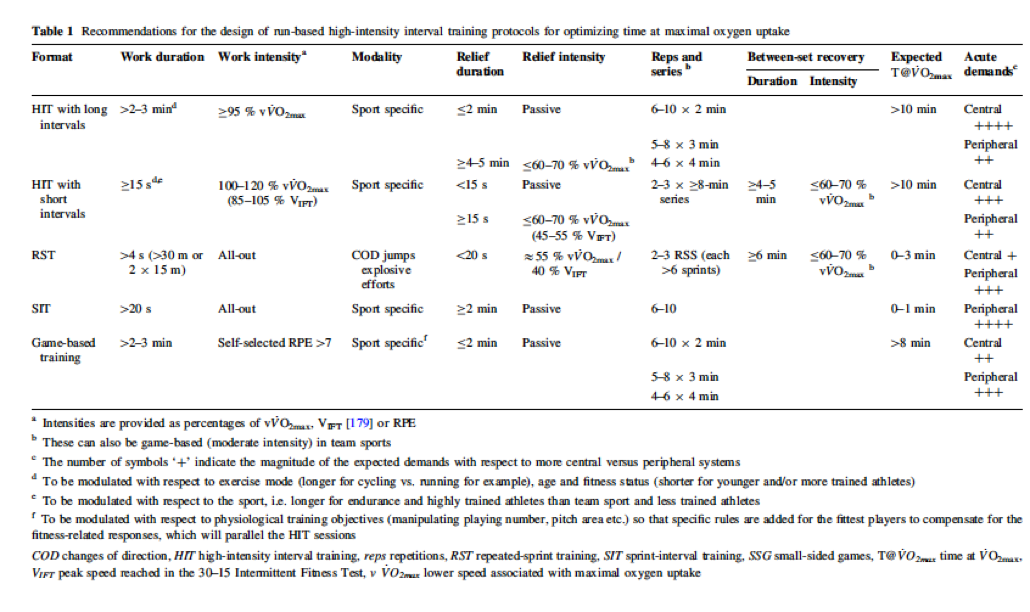

The work interval intensity and duration. This can be short intervals generally < 45 seconds or long intervals 2-8 mins. The intensity of the work interval is generally between 85% – 120% of VO2max or V/Pmax. V/Pmax is the lowest velocity (speed)/power needed to achieve VO2max. This is suggested as a better marker in trained individuals than % of VO2 as it can be a good training reference. It can be assessed using various testing methods such as ramp-like incremental running or cycling tests.

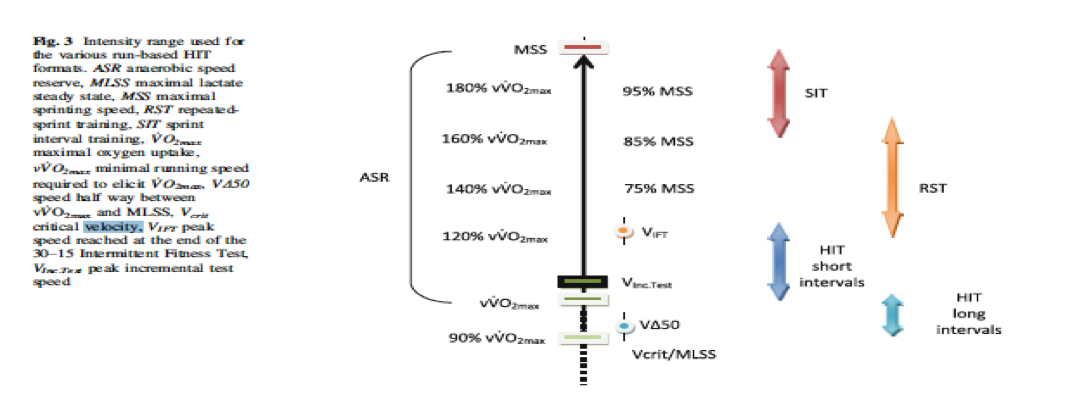

More recently the intensity and duration also includes sprint intervals. These are intense forms of HIIT that include repeated sprint sequences (RSS) lasting 3-7s with rest intervals of <60s or (SIT) with 30s all out efforts with 2-4 mins passive recovery periods as examples. These are commonly referred to as working the ‘red zone’ by athletes which generally means they are working above 90% of their VO2 max. The work intervals can be as high as 120-140% VO2 max or up 120% – 200% functional threshold power (FTP used in cycling). (see fig.3 below).

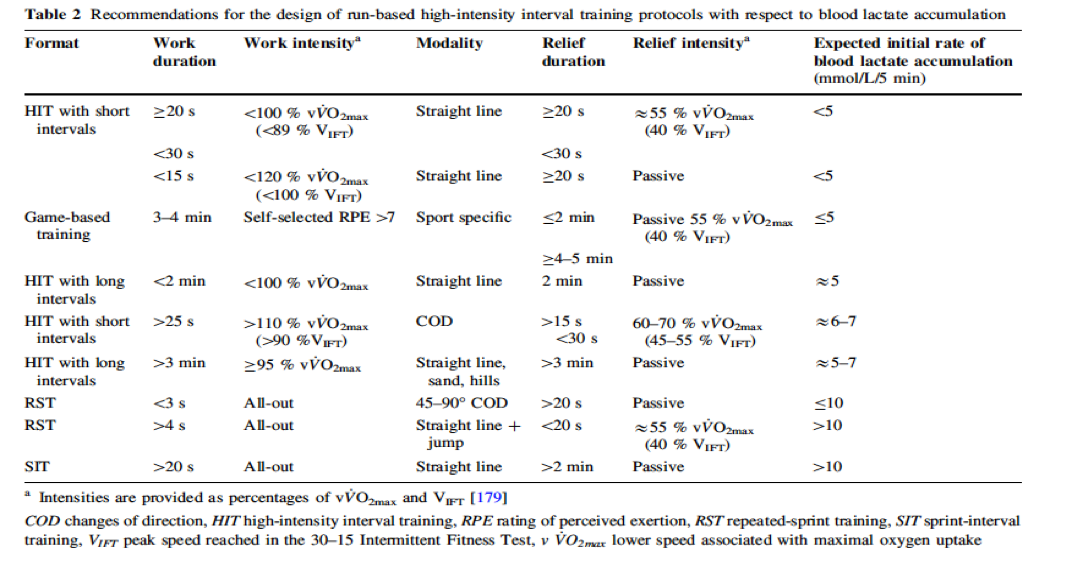

The rest or relief interval intensity and duration can affect the physiological adaptation. These two variables must be considered to maximise the work capacity during the repeated work intervals, and to increase blood flow to accelerate muscle metabolic recovery and muscle lactate oxidation. This will help maintain a level of VO2 to reduce the time to reach VO2 in the following interval. The rest interval can be active or passive. Active is recommended when the work intervals are short. Passive is recommended when the work interval is long but the rest interval short or if the work interval is long and the rest interval longer than 2 mins then active rest interval is recommended. Active should be at submaximal intensity.

Exercise modality can change the stimulus greatly and therefore the adaptive responses. The exercise modality can change the musculo-skeletal & neuro-muscular stress and impact onto the risk benefit ratio of HIIT. i.e.running intervals will initiate a different response to cycle intervals, as will jumps and change of direction training (COD) commonly used as methods of interval training inside.

Number of repetitions and number of series will affect the acute physiological responses to HIIT. When planning the number of reps and series the overall time at VO2 during a training session should be considered. This will impact onto the between series recovery duration and intensity. This will affect the acute response and therefore the residual deficit after the training session and the time to recovery.

Manipulating any of these variables, or more than one of the variables at once, requires detailed periodisation. This will allow you to consider other variables such as anaerobic glycolytic system contribution, blood lactate accumulation, neuromuscular load and musculo-skeletal strain.

Acute Responses & Adaptations.

Understanding the acute responses to the various HIIT formats will help you chose the most appropriate HIIT session to apply for the adaptive response you desire.

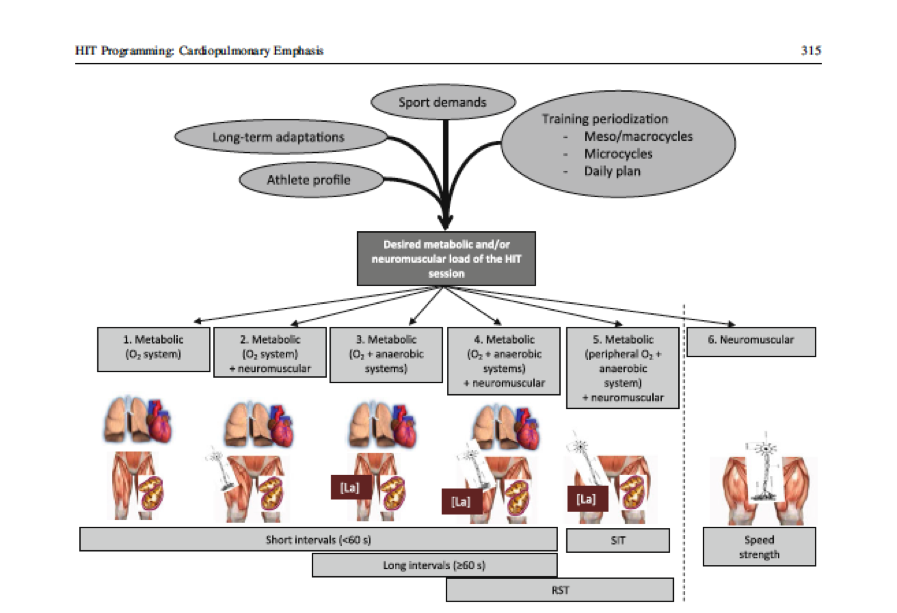

There are six different types of acute response, (Buchheit & Laursen 2013):

- Metabolic response with high requirements form the O2 transport and utilisation and cardiopulmonary systems and type 1 and type 2a muscle fibres

- Metabolic as for 1 but with a degree of neuromuscular strain

- Metabolic as for 1 but with large anaerobic glycolytic energy contribution

- Metabolic as for 3 but with a degree of neuromuscular load

- Metabolic as for 3 with anaerobic glycolytic energy contribution and neuromuscular load

- High predominant neuromuscular strain

(see fig. 1 below. La = blood lactate accumulation. RST = repeated-sprint training, SIT = sprint interval training)

Long-term physiological and performance adaptations to HIIT are highly variable and population dependent. There are large individual differences in these responses between sedentary, recreationally trained or highly trained people. Highly trained people already have a high aerobic capacity, lactate threshold and economy of motion and therefore gains in VO2 max are limited. If ceiling is reached, this doesn’t mean you can’t improve elite endurance performance. The training gains seen in lesser trained individuals may not necessarily apply in the highly trained. Highly-trained individuals have a high aerobic capacity and a high degree of adaptation in a number of physiological variables of the central and peripheral layers of the oxygen delivery system. HIIT elicits performance improvements in highly-trained individual such as elite athletes through enhancements in time spent at VO2, (T@VO2) or Pmax which is peak power achieved at VO2, generally used in cycling or Vmax which is the velocity achieved at VO2 often used by elite runners. In lesser trained individuals gains can be seen in relative VO2 expressed in mls/O2/kg. This is O2 compared to kg of body weight.

Figure 1

Programming

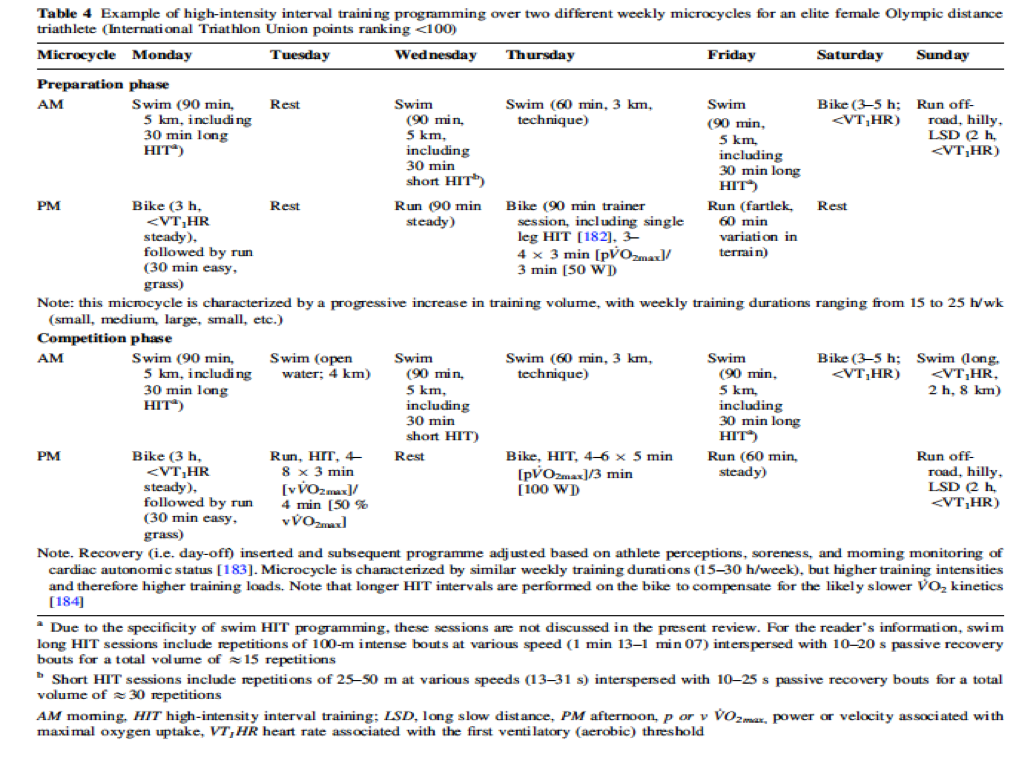

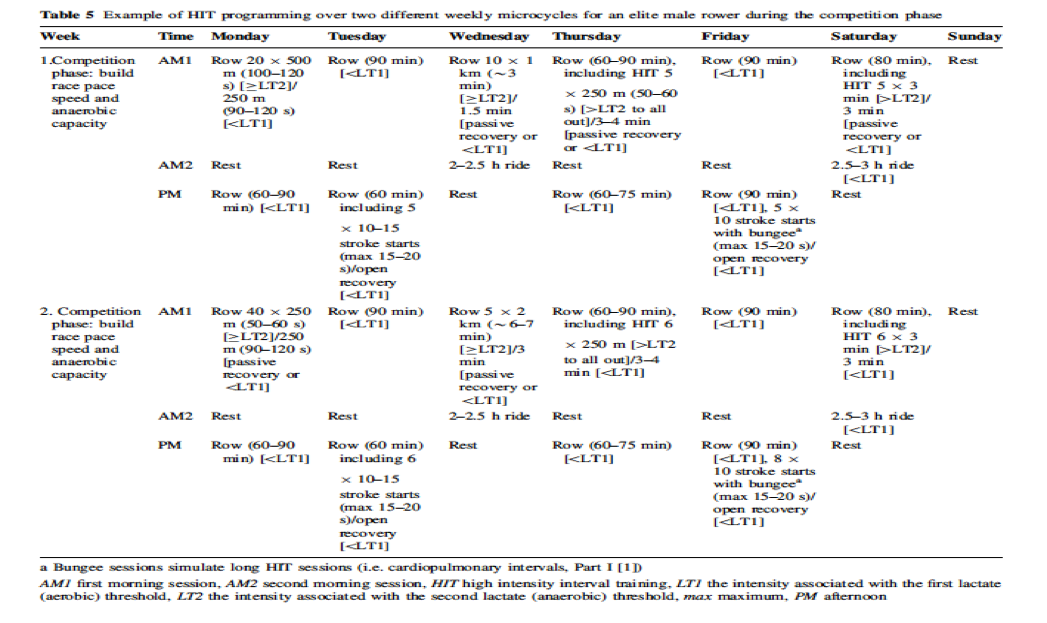

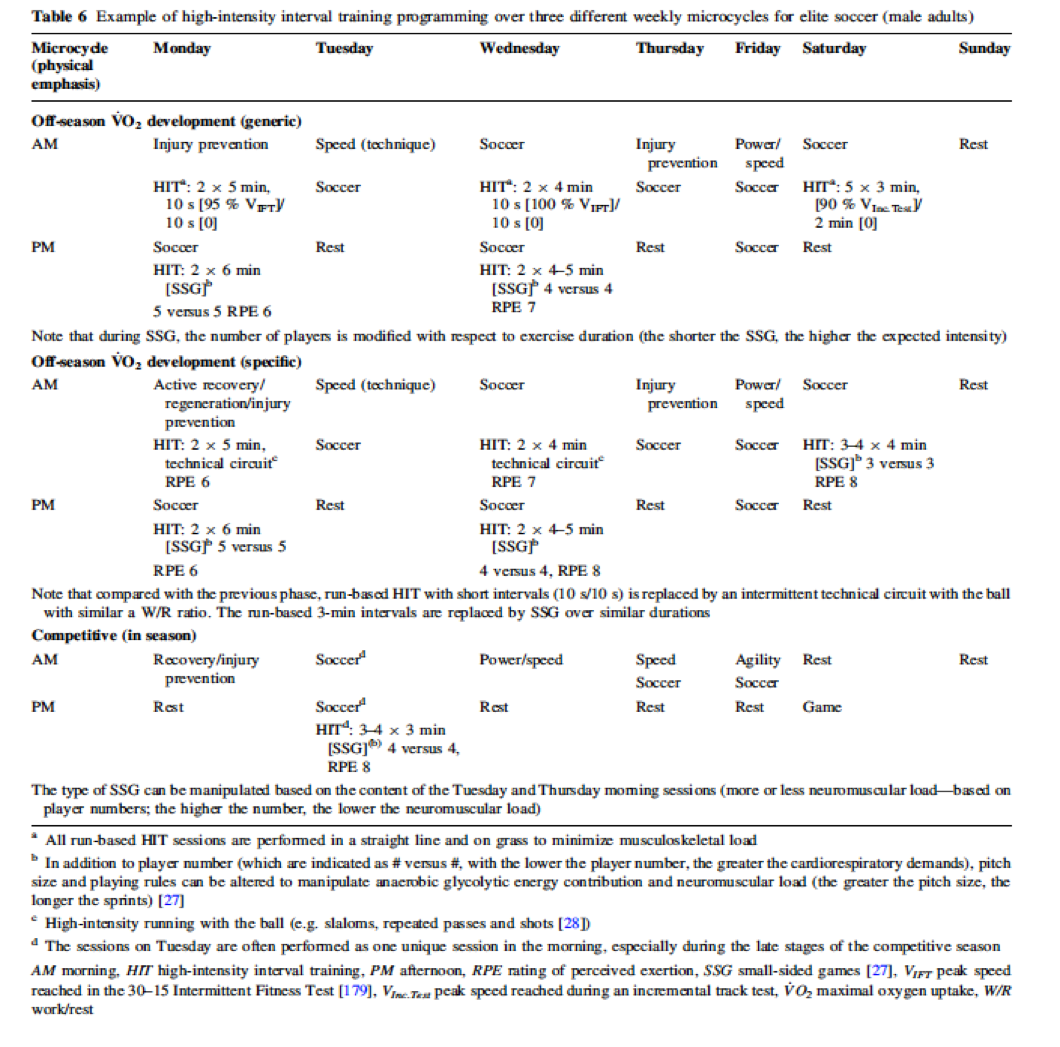

Optimal HIIT programming is dependent on the periodisation of training programmes, training status of the individual and the response that an individual has to a training stimulus. Generally training programmes are periodised to include a base building component, specific training competition phases, tapering and competitive phases. HIIT sessions are generally included after base or stability building and prior to competitive phases. Here are some examples of using HIIT in programming. (see table 1-6)

(Tables & figures Buchheit & Laursen 2013)

If you want to learn more about interval training and scientific training methods book onto the new PT Diploma with Business for as little as £1295.00