Article by Gill Cummings-Bell BA (Hon’s) M.Sc. PGCE. MBA. MIfL

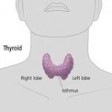

Hypothyroidism (under active thyroid) is a consequence of deficient secretion by the thyroid gland of the thyroid hormones T3 (triiodothyronine) and T4 (thyroxine). Hypothyroidism accounts for up to 80% of thyroid disease cases. (Hyper-thyroidism is not the scope of this article)

Hypothyroidism (under active thyroid) is a consequence of deficient secretion by the thyroid gland of the thyroid hormones T3 (triiodothyronine) and T4 (thyroxine). Hypothyroidism accounts for up to 80% of thyroid disease cases. (Hyper-thyroidism is not the scope of this article)

When working effectively the thyroid hormones travel through the bloodstream and control the rate at which energy in the body is converted (we refer to this as metabolism). The hormones keep the metabolism working at the correct pace. They are also responsible for regulating body temperature and blood calcium levels.

Hypo-thyroidism often presents with non-specific symptoms or symptoms which are masked by other things, such as dry skin, tiredness or weight gain. It can be congenital (at birth) or developed in later life. It is classed as primary or secondary. Primary is a dysfunction of the thyroid gland itself and is usually the low level production of one or more of the hormones or the complete lack of production of one or more of the thyroid hormones. Secondary classification is the pituitary gland (the stimulating gland) or hypothalamic (brain control centre) dysfunction.

Women are much more likely to develop thyroid problems than men. Around 1 in 50 women and 1 in 1000 men develop hypo-thydroidism at some time in their life. Most commonly it develops as an adult women. The most common cause is due to an autoimmune disease called autoimmune thyroiditis. The immune system fails to recognise the gland as being one of your bodies own organs and attacks it with antibodies as if it is a virus. The antibodies then attach themselves to the thyroid and affect its function. It then gradually develops the condition. It can swell and develop into a ‘goitre’. This is then referred to as Hashimoto’s disease.

The condition can also be caused by lack of iodine (not common in a normal UK diet), a side effect of some medications, a pituitary gland problem or a congenital defect (1 in 400 babies are born without a thyroid gland).

Thyroid Physiology

The hypothalamus (brain), pituitary gland and the thyroid gland all play a part in the feedback and regulatory mechanisms involved in the production of thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) from the thyroid gland. It’s a cascade of events leading to full function.

- Thyroid releasing hormone (TRH) is secreted by the hypothalamus (brain) and stimulates the production of the thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) from the anterior pituitary gland.

- TSH then stimulates the production and release of T4 from the thyroid gland and its conversion hormone T3. T3 is the hormone directly used by the cells

- Once released, T4 and T3 then exert a negative feedback loop mechanism on TSH production. In other words it signals to the pituitary gland to switch off the production of TSH indicating that everything is functioning normally and effectively

- T4 is the main hormone produced by the thyroid.

- T3 is mainly produced by peripheral conversion of T4.

- T3 and T4 both act to increase cell metabolism. This is the turnover of ATP in each cell.

When the thyroid gland doesn’t produce enough thyroxine T4 or conversion to T3 is low, it causes many of the functions of the body to slow down including blood functions.

Symptoms

Symptoms may present as severe or mild sub clinical and can often be masked i.e. tiredness can be attributed to other causes. The symptoms can often be missed and can sometimes be attributed to the aging process by mistake. Symptoms may be mild at first and increase over a number of years also making them easy to miss as you get used to living with them

| Common Symptoms | Common Symptoms |

|

|

How is it diagnosed?

Thyroid function testing by blood test is the most common method of diagnosis. This is an endocrine (hormone) function test. Over 10 million tests per year are conducted in the UK at a cost of £30 million. It can be a problematic test and will not necessarily diagnose the condition. The mechanism for use of the thyroid hormones is intra-cellular and not utilized by the blood and the test does not test this. There can also be a problem with low blood volume in a hypo-thyroid individual therefore blood panel readings will appear higher.

TSH – The pituitary gland produces the hormone TSH (see above physiology), which is measured in the blood. This hormone stimulates the production of thyroxine (T4). If the levels of TSH are elevated this means the levels of thyroxine are low and the TSH levels are trying to encourage the thyroid to make more.

T4 – if T4 levels are low it is confirmed.

Sometimes you can have normal levels of T4 produced by they thyroid but elevated TSH which means the pituitary is working harder to stimulate the thyroid. This means you may well develop hyop-thryoidism in the future.

Getting an accurate test to diagnose hypo-thyroidism can be difficult. After doing tests your doctor may tell you that you are in the “normal range”, even if you still have hypo-thyroid symptoms and know something is very wrong in your body.

This could be because you are at the very edge of the range, either at the bottom or at the top, you could be classed as “borderline”. It is difficult to diagnose normal range. Unless you were tested prior to being ill its impossible to know what ‘normal range’ for you would be.

The blood test may not pick up dysfunction at cellular level or be testing level conversion to T3. If you are not converting from T4 to T3 or if your cells are not taking up the T3 normally, your T4 levels and your TSH levels will still show as normal.

Thyroid UK believe that you need to know your Free T3 level because this will often show low if you are not converting, and high if you have blocked receptor cells. Even if you are converting, the body needs the extra T3 that a normal thyroid produces.

It is worth asking your doctor to conduct further testing and ensure that they look at the global condition and take your symptoms into consideration.

Treatment

The treatment is to take thyroxine replacement therapy each day to normalize the TSH and obtain a positive thyroid state in the body. To obtain this, FT4 and TT4 have to be maintained at, or just above, the upper reference interval”. This replaces the thyroxine that your thyroid gland is not making. Most people feel much better soon after starting treatment however it can take some time to get the dosage correct. The British Thyroid Foundation state that the correct dose is what resumes good health.

How Can Nutrition Help?

As with all bodily functions (you are what you eat), your diet plays a major role in the health of your thyroid. There are some specific nutrients that your thyroid needs for effective function and it’s important to include them in your diet:

As with all bodily functions (you are what you eat), your diet plays a major role in the health of your thyroid. There are some specific nutrients that your thyroid needs for effective function and it’s important to include them in your diet:

- Iodine: Your thyroid cells absorb iodine, which it uses to make the T3 and T4 hormones. Iodine deficiency is not typical in the UK because of the prevalent use of iodized salt.

- Selenium: This mineral is an antioxidant mineral and is critical for the proper functioning of your thyroid gland, and is used to produce and regulate the T3 hormone.

Selenium can be found in shrimp, snapper, tuna, cod, halibut, calf’s liver, button and shitake mushrooms and Brazil nuts, sunflower seeds, rice, wheat and oatbran

- Zinc and Iron: These are needed in tiny amounts for healthy thyroid function, metabolic rate and immune function. Low levels of zinc have been linked to low levels of TSH, whereas iron deficiency has been linked to decreased thyroid efficiency.

Foods such as prawns, lamb, grass fed beef, calf’s liver, spinach, mushrooms, sunflower, pumpkin and sesame seeds can help provide these trace metals in your diet.

- Omega-3 Fats: These essential fats (fish oils), play an important role in thyroid function, and may help your cells become sensitive to thyroid hormone.

- A C E Antioxidants and B Vitamins: The antioxidant vitamins A, C and E can help your body combat free radical damage caused by oxidative stress that may damage the thyroid. In addition, B vitamins help to manufacture thyroid hormone and play an important role in healthy thyroid function.

Vitamin A or retinol is found in liver, animal fats, oils such as olive and soy, cereal grain germs like wheatgerm and egg yolks. Fruit and vegetables contain beta-carotene in their yellow and orange pigments, which is converted to vitamin A in your body.

B-complex vitamins. Most of the B-complex vitamins are found in pork, grains, vegetables and milk. Thiamine is found in pork, cheese, dried fruit and peas; riboflavin in small quantities in milk, eggs and mushrooms; and niacin in beef, milk, wheat flour and eggs. Pyridoxine can be found in a wide variety of foods including chicken and turkey, eggs, oatmeal, rice, peanuts and bread. Vitamin B12 is present in most meats, seaweed, salmon, milk, yeast extract and eggs.

Vitamin C or ascorbic acid is found in fresh fruit and vegetables, sweet potatoes and fresh milk. The foods highest in vitamin C are: black currants at 220 mg per 100 g, guavas at 180 mg, bell peppers at 100 mg, cauliflower at 120 mg, cabbage at 120 mg and parsley at 150 mg.

Vitamin E is found in high quantities in nuts, seeds and vegetable oils such as olive and soy.

Following a healthy eating plan for hormonal balance is the key to thyroid health. This includes oily fish, lean meats, lots of vegetables particularly root vegetables, seeds and nuts. For further information or an eating plan to follow contact www.drummondclinic.co.uk

How can exercise help?

Regular exercise is important to maintain good health. It is especially important in the treatment of hypo-thyroidism to maintain a healthy weight, increase tissue sensitivity to the thyroid hormone, stimulate normal hormone secretion and improve respiratory function. Exercise can also help control stress, which can help normalise hormone control. Exercise will help combat the symptoms of fatigue and improve the metabolism.

An exercise regime of between 15-20 minutes per day initially will be beneficial with hypo-thyroidism, increasing as you progress to 40 minutes per day.

This exercise should include cardiovascular training and muscle conditioning.

Cardio-vascular

Exercising at low intensity can increase blood levels of T3, T4 and TSH. This can include interval training, aerobics, dance, walking, swimming and cycling.

Muscle Conditioning

Improving muscle tone particularly in the slow twitch muscle fibres (type 1) which are the aerobic fibres and the fast twitch type 2A which are also aerobic will help increase metabolism. Low to moderate resistance training working compound functional movement patterns is the most effective form of training.

Contact www.drummondeducation.com to join the nutrition course or personal training course and learn more about this area and metabolic exercise training.